Bytecode

Intent

Allows encoding behavior as instructions for a virtual machine.

Explanation

Real world example

A team is working on a new game where wizards battle against each other. The wizard behavior needs to be carefully adjusted and iterated hundreds of times through playtesting. It’s not optimal to ask the programmer to make changes each time the game designer wants to vary the behavior, so the wizard behavior is implemented as a data-driven virtual machine.

In plain words

Bytecode pattern enables behavior driven by data instead of code.

Gameprogrammingpatterns.com documentation states:

An instruction set defines the low-level operations that can be performed. A series of instructions is encoded as a sequence of bytes. A virtual machine executes these instructions one at a time, using a stack for intermediate values. By combining instructions, complex high-level behavior can be defined.

Programmatic Example

One of the most important game objects is the Wizard class.

1@AllArgsConstructor

2@Setter

3@Getter

4@Slf4j

5public class Wizard {

6

7 private int health;

8 private int agility;

9 private int wisdom;

10 private int numberOfPlayedSounds;

11 private int numberOfSpawnedParticles;

12

13 public void playSound() {

14 LOGGER.info("Playing sound");

15 numberOfPlayedSounds++;

16 }

17

18 public void spawnParticles() {

19 LOGGER.info("Spawning particles");

20 numberOfSpawnedParticles++;

21 }

22}

Next, we show the available instructions for our virtual machine. Each of the instructions has its own semantics on how it operates with the stack data. For example, the ADD instruction takes the top two items from the stack, adds them together and pushes the result to the stack.

1@AllArgsConstructor

2@Getter

3public enum Instruction {

4

5 LITERAL(1), // e.g. "LITERAL 0", push 0 to stack

6 SET_HEALTH(2), // e.g. "SET_HEALTH", pop health and wizard number, call set health

7 SET_WISDOM(3), // e.g. "SET_WISDOM", pop wisdom and wizard number, call set wisdom

8 SET_AGILITY(4), // e.g. "SET_AGILITY", pop agility and wizard number, call set agility

9 PLAY_SOUND(5), // e.g. "PLAY_SOUND", pop value as wizard number, call play sound

10 SPAWN_PARTICLES(6), // e.g. "SPAWN_PARTICLES", pop value as wizard number, call spawn particles

11 GET_HEALTH(7), // e.g. "GET_HEALTH", pop value as wizard number, push wizard's health

12 GET_AGILITY(8), // e.g. "GET_AGILITY", pop value as wizard number, push wizard's agility

13 GET_WISDOM(9), // e.g. "GET_WISDOM", pop value as wizard number, push wizard's wisdom

14 ADD(10), // e.g. "ADD", pop 2 values, push their sum

15 DIVIDE(11); // e.g. "DIVIDE", pop 2 values, push their division

16 // ...

17}

At the heart of our example is the VirtualMachine class. It takes instructions as input and

executes them to provide the game object behavior.

1@Getter

2@Slf4j

3public class VirtualMachine {

4

5 private final Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<>();

6

7 private final Wizard[] wizards = new Wizard[2];

8

9 public VirtualMachine() {

10 wizards[0] = new Wizard(randomInt(3, 32), randomInt(3, 32), randomInt(3, 32),

11 0, 0);

12 wizards[1] = new Wizard(randomInt(3, 32), randomInt(3, 32), randomInt(3, 32),

13 0, 0);

14 }

15

16 public VirtualMachine(Wizard wizard1, Wizard wizard2) {

17 wizards[0] = wizard1;

18 wizards[1] = wizard2;

19 }

20

21 public void execute(int[] bytecode) {

22 for (var i = 0; i < bytecode.length; i++) {

23 Instruction instruction = Instruction.getInstruction(bytecode[i]);

24 switch (instruction) {

25 case LITERAL:

26 // Read the next byte from the bytecode.

27 int value = bytecode[++i];

28 // Push the next value to stack

29 stack.push(value);

30 break;

31 case SET_AGILITY:

32 var amount = stack.pop();

33 var wizard = stack.pop();

34 setAgility(wizard, amount);

35 break;

36 case SET_WISDOM:

37 amount = stack.pop();

38 wizard = stack.pop();

39 setWisdom(wizard, amount);

40 break;

41 case SET_HEALTH:

42 amount = stack.pop();

43 wizard = stack.pop();

44 setHealth(wizard, amount);

45 break;

46 case GET_HEALTH:

47 wizard = stack.pop();

48 stack.push(getHealth(wizard));

49 break;

50 case GET_AGILITY:

51 wizard = stack.pop();

52 stack.push(getAgility(wizard));

53 break;

54 case GET_WISDOM:

55 wizard = stack.pop();

56 stack.push(getWisdom(wizard));

57 break;

58 case ADD:

59 var a = stack.pop();

60 var b = stack.pop();

61 stack.push(a + b);

62 break;

63 case DIVIDE:

64 a = stack.pop();

65 b = stack.pop();

66 stack.push(b / a);

67 break;

68 case PLAY_SOUND:

69 wizard = stack.pop();

70 getWizards()[wizard].playSound();

71 break;

72 case SPAWN_PARTICLES:

73 wizard = stack.pop();

74 getWizards()[wizard].spawnParticles();

75 break;

76 default:

77 throw new IllegalArgumentException("Invalid instruction value");

78 }

79 LOGGER.info("Executed " + instruction.name() + ", Stack contains " + getStack());

80 }

81 }

82

83 public void setHealth(int wizard, int amount) {

84 wizards[wizard].setHealth(amount);

85 }

86 // other setters ->

87 // ...

88}

Now we can show the full example utilizing the virtual machine.

1 public static void main(String[] args) {

2

3 var vm = new VirtualMachine(

4 new Wizard(45, 7, 11, 0, 0),

5 new Wizard(36, 18, 8, 0, 0));

6

7 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("LITERAL 0"));

8 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("LITERAL 0"));

9 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("GET_HEALTH"));

10 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("LITERAL 0"));

11 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("GET_AGILITY"));

12 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("LITERAL 0"));

13 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("GET_WISDOM"));

14 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("ADD"));

15 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("LITERAL 2"));

16 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("DIVIDE"));

17 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("ADD"));

18 vm.execute(InstructionConverterUtil.convertToByteCode("SET_HEALTH"));

19 }

Here is the console output.

16:20:10.193 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed LITERAL, Stack contains [0]

16:20:10.196 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed LITERAL, Stack contains [0, 0]

16:20:10.197 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed GET_HEALTH, Stack contains [0, 45]

16:20:10.197 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed LITERAL, Stack contains [0, 45, 0]

16:20:10.197 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed GET_AGILITY, Stack contains [0, 45, 7]

16:20:10.197 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed LITERAL, Stack contains [0, 45, 7, 0]

16:20:10.197 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed GET_WISDOM, Stack contains [0, 45, 7, 11]

16:20:10.197 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed ADD, Stack contains [0, 45, 18]

16:20:10.197 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed LITERAL, Stack contains [0, 45, 18, 2]

16:20:10.198 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed DIVIDE, Stack contains [0, 45, 9]

16:20:10.198 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed ADD, Stack contains [0, 54]

16:20:10.198 [main] INFO com.iluwatar.bytecode.VirtualMachine - Executed SET_HEALTH, Stack contains []

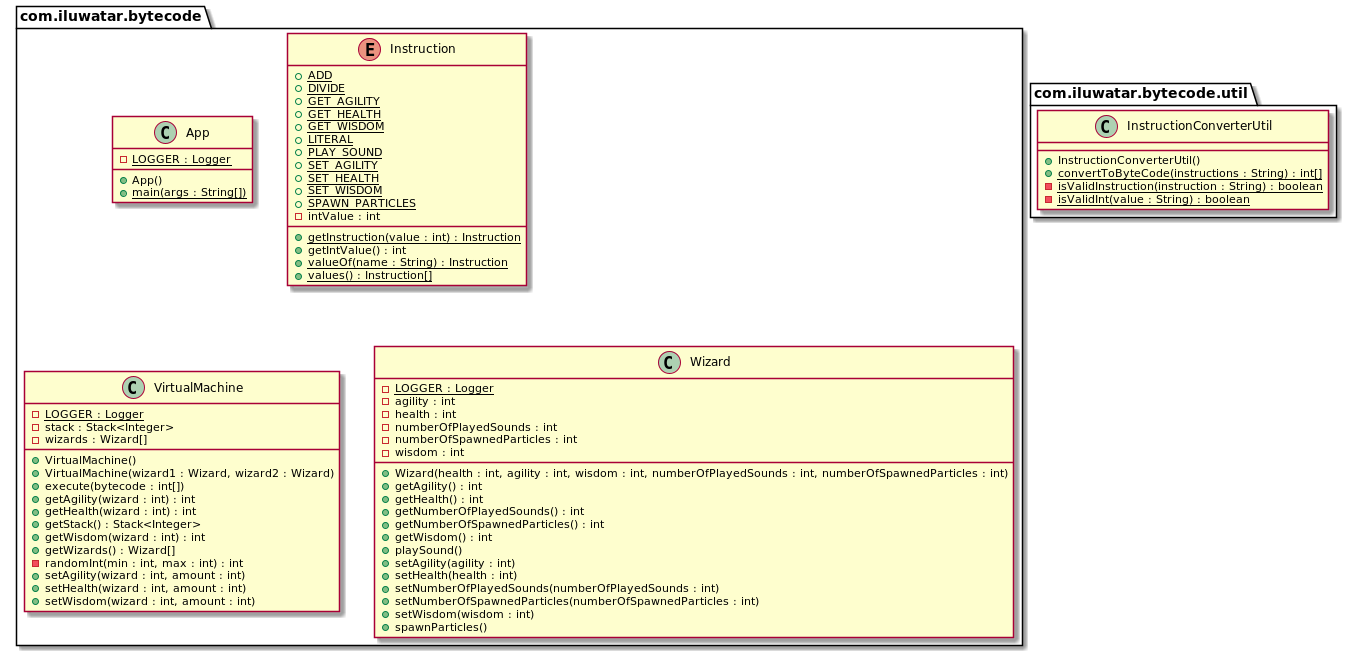

Class diagram

Applicability

Use the Bytecode pattern when you have a lot of behavior you need to define and your game’s implementation language isn’t a good fit because:

- It’s too low-level, making it tedious or error-prone to program in.

- Iterating on it takes too long due to slow compile times or other tooling issues.

- It has too much trust. If you want to ensure the behavior being defined can’t break the game, you need to sandbox it from the rest of the codebase.